Blog Post

Bretton Woods—Why the dollar?

Bretton Woods Committee

|

Thu, Apr 4, 2024

Body

The Bretton Woods Conference will celebrate its 80th anniversary this year. The conference can be seen to have formalised the role of the U.S. dollar as the dominant currency in the international monetary system. This remains so to this day as does the considerable controversy it produced. Yet at the time when the conference started on 1 July 1944, it was not at all clear that the dollar would be endowed witch such role. The spirit then was that multiple currencies should be used in international payments with the suggested rationale for this as valid today as it was then.

The Bretton Woods conference produced a unique arrangement with the establishment of the International Monetary Fund, creating a framework for cooperation whereby countries abandoned their ability to adjust the value of their national currencies unilaterally. All currencies were fixed to the dollar (par values) and the dollar was fixed to gold. Any change in par values could be made only after consultation with the Fund and any change greater than 10 percent required the Fund to concur. This provided the legal basis for the centrality of the dollar. On 23 July 1944, following the end of the conference and publication of the Articles, the New York Times reported: “The American dollar thus obtains international recognition, on paper as in fact, as the world currency.”

The ascent of the dollar in particular during the post-war era was in large part due to the fact that the dollar was one of the few currencies convertible into gold. Other international payments had to clear in gold or a gold convertible currency (e.g. sterling) and many European currencies became convertible only towards the end of the 1950s. During this time, most monetary gold was in the U.S.

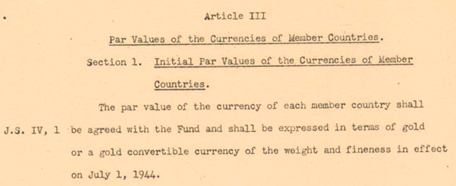

But the dollar was not meant to become the world currency at Bretton Woods. Earlier documents explored ideas of international currencies but never mentioned the dollar. They prominently included the ideas of U.K. delegation chairman at Bretton Woods, John Maynard Keynes, on bancor and of U.S. treasury official and main architect of Bretton Woods Harry, Dexter White, on unitas. The Joint Statement (J.S.) between the U.S. and the U.K., a compromise between their respective proposals, was released on April 21, 1944. This statement laid the groundwork for an agreement on the IMF and introduced the concept of "gold convertible exchange," later modified to "gold convertible currency" in the working documents at Bretton Woods (Figure).

Figure. IMF Articles of Agreement draft 23 June 1944

It would appear the dollar became the central currency at Bretton Woods by accident. In a meeting of Commission 1 [dealing with the International Monetary Fund] on 13 July 1944, Ardeshir Darabshaw Shroff with the Indian delegation raised the following question to White, Commission Chairman:* “I think it is high time that the USA delegation give us a definition of gold and gold convertible exchange.” Edward Bernstein of the U.S. delegation replied: “Mr Chairman, it might be possible to give a definition of gold convertible exchange which would be satisfactory to everyone here, but it would involve a long discussion. […] There are a number of other currencies, which can be used to purchase dollars without restriction, and these dollars in turn can be used to purchase gold. The definition of gold convertible currency might include such currencies, but the practical importance of holdings of the countries represented here is so small that it has been felt it would be easier for this purpose to regard the United States dollar as what was intended when we speak of gold convertible exchange.” A special committee was then tasked with rewriting the definition in the draft documents. It was a clarification question that led to enshrine the role of the dollar at Bretton Woods.

Bretton Woods wanted all currencies to be used in international payments. In a memorandum to Committee 2 [Operations of the Fund] of Commission 1 about the use of Fund resources of around 12 July 1944:** “The Fund must be in a position to dispose of its franc balances in meeting payments due to France, its guilder balances in meeting payments due to the Netherlands, etc. There is no doubt that the provision can be made in the Fund proposal to facilitate the use of all of the currencies in the Fund in meeting balances of payments.” This reflects a fundamental understanding about the principle that the use of few currencies would pose undue constraints on the effective operations of the Fund. Dependence on such currencies would also have produced an overly skewed demand for those currencies undermining exchange rate stability. It manifested itself in the scare currency clause of the Articles (Article VII) outlining that insufficient access to and liquidity in a given currency poses a major challenge for meeting international payments obligations.

The dominance of the dollar has long been a concern of many countries. The IMF’s later efforts to establish the Special Drawing Rights (SDR) as the main reserve currency are to be seen in that same light. More recently, renewed initiatives are under way to promote the use of additional currencies—local currency international payments like BIS project mBridge—to advance diversification in international payments. 80 years on, Bretton Woods may still offer the best guidance for the direction of the international monetary system.

* Meeting transcripts from Kurt Schuler and Andrew Rosenberg, The Bretton Woods transcripts, 2012.

** Idem. The date of the memorandum is not clear.

Ousmène Jacques Mandeng, Director, Economics Advisory Ltd, Visiting Fellow, London School of Economics and Political Science

To continue reading at

Bretton Woods Committee

, click here.

Bretton Woods—Why the dollar?

Bretton Woods Committee | Thu, Apr 4, 2024

The Bretton Woods Conference will celebrate its 80th anniversary this year. The conference can be seen to have formalised the role of the U.S. dollar as the dominant currency in the international monetary system. This remains so to this day as does the considerable controversy it produced. Yet at the time when the conference started on 1 July 1944, it was not at all clear that the dollar would be endowed witch such role. The spirit then was that multiple currencies should be used in international payments with the suggested rationale for this as valid today as it was then.

The Bretton Woods conference produced a unique arrangement with the establishment of the International Monetary Fund, creating a framework for cooperation whereby countries abandoned their ability to adjust the value of their national currencies unilaterally. All currencies were fixed to the dollar (par values) and the dollar was fixed to gold. Any change in par values could be made only after consultation with the Fund and any change greater than 10 percent required the Fund to concur. This provided the legal basis for the centrality of the dollar. On 23 July 1944, following the end of the conference and publication of the Articles, the New York Times reported: “The American dollar thus obtains international recognition, on paper as in fact, as the world currency.”

The ascent of the dollar in particular during the post-war era was in large part due to the fact that the dollar was one of the few currencies convertible into gold. Other international payments had to clear in gold or a gold convertible currency (e.g. sterling) and many European currencies became convertible only towards the end of the 1950s. During this time, most monetary gold was in the U.S.

But the dollar was not meant to become the world currency at Bretton Woods. Earlier documents explored ideas of international currencies but never mentioned the dollar. They prominently included the ideas of U.K. delegation chairman at Bretton Woods, John Maynard Keynes, on bancor and of U.S. treasury official and main architect of Bretton Woods Harry, Dexter White, on unitas. The Joint Statement (J.S.) between the U.S. and the U.K., a compromise between their respective proposals, was released on April 21, 1944. This statement laid the groundwork for an agreement on the IMF and introduced the concept of "gold convertible exchange," later modified to "gold convertible currency" in the working documents at Bretton Woods (Figure).

Figure. IMF Articles of Agreement draft 23 June 1944

It would appear the dollar became the central currency at Bretton Woods by accident. In a meeting of Commission 1 [dealing with the International Monetary Fund] on 13 July 1944, Ardeshir Darabshaw Shroff with the Indian delegation raised the following question to White, Commission Chairman:* “I think it is high time that the USA delegation give us a definition of gold and gold convertible exchange.” Edward Bernstein of the U.S. delegation replied: “Mr Chairman, it might be possible to give a definition of gold convertible exchange which would be satisfactory to everyone here, but it would involve a long discussion. […] There are a number of other currencies, which can be used to purchase dollars without restriction, and these dollars in turn can be used to purchase gold. The definition of gold convertible currency might include such currencies, but the practical importance of holdings of the countries represented here is so small that it has been felt it would be easier for this purpose to regard the United States dollar as what was intended when we speak of gold convertible exchange.” A special committee was then tasked with rewriting the definition in the draft documents. It was a clarification question that led to enshrine the role of the dollar at Bretton Woods.

Bretton Woods wanted all currencies to be used in international payments. In a memorandum to Committee 2 [Operations of the Fund] of Commission 1 about the use of Fund resources of around 12 July 1944:** “The Fund must be in a position to dispose of its franc balances in meeting payments due to France, its guilder balances in meeting payments due to the Netherlands, etc. There is no doubt that the provision can be made in the Fund proposal to facilitate the use of all of the currencies in the Fund in meeting balances of payments.” This reflects a fundamental understanding about the principle that the use of few currencies would pose undue constraints on the effective operations of the Fund. Dependence on such currencies would also have produced an overly skewed demand for those currencies undermining exchange rate stability. It manifested itself in the scare currency clause of the Articles (Article VII) outlining that insufficient access to and liquidity in a given currency poses a major challenge for meeting international payments obligations.

The dominance of the dollar has long been a concern of many countries. The IMF’s later efforts to establish the Special Drawing Rights (SDR) as the main reserve currency are to be seen in that same light. More recently, renewed initiatives are under way to promote the use of additional currencies—local currency international payments like BIS project mBridge—to advance diversification in international payments. 80 years on, Bretton Woods may still offer the best guidance for the direction of the international monetary system.

* Meeting transcripts from Kurt Schuler and Andrew Rosenberg, The Bretton Woods transcripts, 2012.

** Idem. The date of the memorandum is not clear.

Ousmène Jacques Mandeng, Director, Economics Advisory Ltd, Visiting Fellow, London School of Economics and Political Science